It was recently reported that a team sponsored by Whyte & Mackay had recovered several cases of whisky left behind by Shackleton and his crew in Antarctica (they will apparently try to recreate the particular batch found). The fascinating story led me to spend part of this last week reading Shackleton’s book on his retelling of the failed expedition.

Interestingly there is no mention of the whisky in it, and there are only a few references to other types of alcohol which only seemed to be used rarely for toasts, holidays, and cooking.

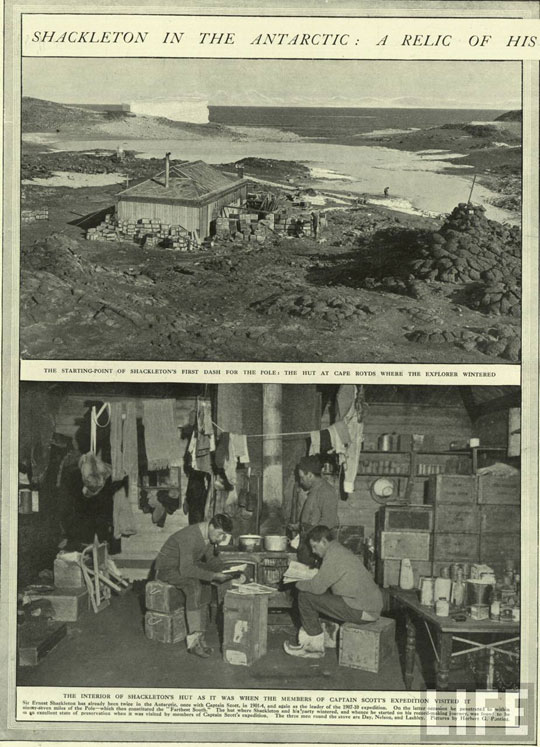

From a section where he is describing part of the cabin at Cape Royds (where the cases were found):

My room contained the bulk of our library, the chronometers, the chronometer watches, barograph, and the electric recording thermometer; there was ample room for a table and the whole made a most comfortable cabin. On the roof we stowed those of our scientific instruments which were not in use such as theodolites, spare thermometers, dip circles, &c. The gradual accumulation of weight produced a distinct sag in the roof, which sometimes seemed to threaten collapse as I sat inside, but no notice was taken and nothing happened. On the roof of the dark room we stowed all our photographic gear and our few cases of wine, which were only drawn upon on special occasions such as Mid winter Day. pg. 85

Maybe the wine above was the whisky? Earlier he also describes a situation where brandy is fed to one of the ponies named Chinaman, who had fallen in ice cold water:

Mackay started to try and get the pony Chinaman across the crack when it was only about six inches wide, but the animal suddenly took fright, reared up on his hind legs, and backing towards the edge of the floe, which had at that moment opened to a width of a few feet, fell bodily into the ice cold water. It looked as if it was all over with poor Chinaman, but Mackay hung on to the head rope, and Davis, Mawson, Michell and one of the sailors who were on the ice close by rushed to his assistance. The pony managed to get his fore feet on to the edge of the ice-floe. After great difficulty a rope sling was passed underneath him, and then by tremendous exertion he was lifted up far enough to enable him to scramble on to the ice. There he stood, wet and trembling in every limb. A few seconds later the floe closed up against the other one. It was providential that it had not done so during the time that the pony was in the water, for in that case the animal would inevitably have been squeezed to death between the two huge masses of ice. A bottle of brandy was thrown on to the ice from the ship, and half its contents were poured down Chinaman’s throat. pg. 63

Chinaman ended up being the weakest of the horses and was the first to be killed for food:

It can be imagined that the cook for the week had no easy task. His work became more difficult still when we were using ponymeat, for the meat and blood, when boiled up, made a delightful broth, while the fragments of meat sunk to the bottom of the pot. The liquor was much the better part of the dish, and no one had much relish for the little dice of tough and stringy meat, so the cook had to be very careful indeed. Poor old Chinaman was particularly tough and stringy horse. pg. 230

In those days, explorers used animals brought along as transportation and when needed, as a source of food. Shackleton describes this process in detail on pg. 168 if you’re curious.

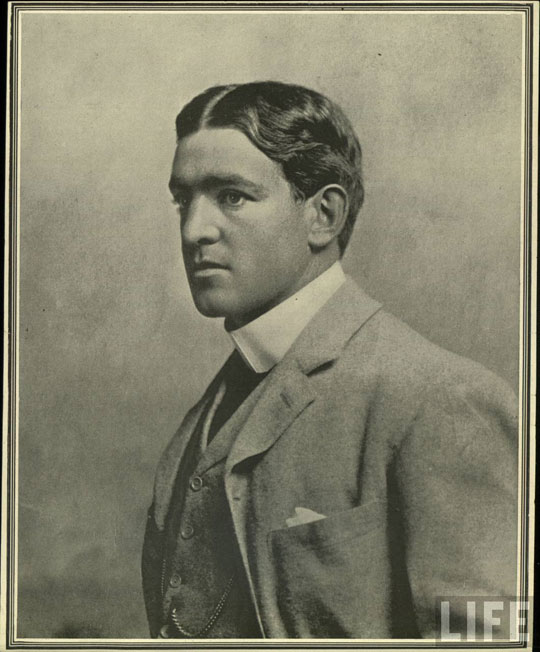

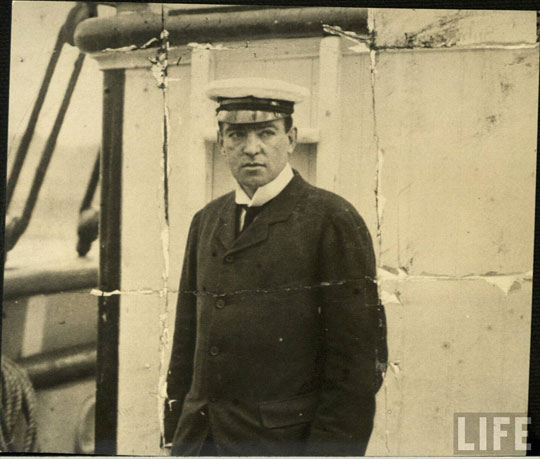

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton

Comments are closed.