The Strand Magazine, published in 1902, reporting on the newest fad of the time – the Panama hat:

One hundred pounds for a straw hat! Enough with which to take a three months’ holiday, enough to keep your son a year at college, enough to buy a small farm. And yet so astute a financier as Mr. Lyman Gage, ex-Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, recently paid that sum for an extra-fine Panama hat, and reckoned, moreover, that he had made a good bargain. King Edward VII also is reported to have paid a Bond Street hatter £90 to secure “the best Panama in London”; while Jean de Reszke, the noted tenor, has paid the topmost price—something under £120 — to procure a similar object in America. Ex – Mayor Van Wyck, of New York, is chuckling over his success in securing a Panama which dealers have told him is superior in quality to either King Edward’s or the one owned by Jean de Reszke. He paid only £50.

These instances of extravagance are not mentioned as a reflection upon the perpetrators, but merely to illustrate the extent of “the Panama hat craze,” one of the most expensive fashions ever adopted by men. Expensive, because a Panama of even medium quality cannot be had for less than £5, and if you aim at having one that maybe tucked away in a vest pocket like a lead pencil, or slipped through a finger-ring, the price is, to most persons, prohibitive. In spite of this costliness, however, Panama hats are being dispatched from South America absolutely in ship-loads, and about half the population of Ecuador are engaged in supplying hat luxuries for the men of Europe and America.

The craze began last year, and appeared to be only transient; but enterprising merchants foretold that this summer would find a demand far greater than the supply, and they accordingly put in their orders about six months ago. Since then the Panama hat industry has become more lucrative than any other in that part of South America adjoining the Isthmus, and with the prospect of making a fortune in a few years many planters have abandoned the raising of coffee and rice. The mountain passes of the Andes, from Chimborazo northward, are crowded, day and night, with long columns of pack-mules and ox-carts bearing their precious burden to Panama, which is the clearing-house for hats. The streets of Panama itself are flanked with the establishments of hatbrokers, and half the city is engaged, one way or other, in helping to further this American “craze.”In all the pages of history you will, perhaps, find no account of a fad that was at the same time so costly as this one and yet so generally adopted, not even when plumed knights and velvet-clothed courtiers trod the earth. In their heyday a considerable sum of money was, no doubt, paid for the picturesque “Gainsborough,” expensively decorated, which was affected by the men of that period; but it is safe to say that not even the extravagant Louis XIV paid for his head-dress the price of the best Panama.

In our time it has been almost the exclusive privilege of women to spend large sums of money on hats, and it is not uncommon to hear of a Parisian “creation ” selling for a thousand dollars. With the fashion, nowadays, of occasionally wearing diamonds or other precious gems on a head-dress, there is practically no limit to the depth that a woman might plunge in indulging in this luxury. The fad of wearing real lace that is affected to day is also a costly one. A smartly-dressed woman whose ambition is to be in the swim of society will often wear two or three yards of Irish point-lace that costs, perhaps, £So a yard. It is this sort of thing that gives a father or a husband heart disease, a tragedy that has been so useful to joke-writers and knock-about comedians.

But the tables are now reversed, and humorists to be up-to-date must regild one of their stock commodities. It is the women now who gasp with astonishment when the head of the house comes home with a little wisp of straw which he cheerfully proclaims has cost him something like a hundred pounds. Not only that, but he has the effrontery to boast of the purchase and goes strutting about because Brown or Jones has a Panama hat that is woven in two pieces while his, proud man, has never a seam!

At first sight the Panama hat “craze” would appear to be a lavish folly taken up because of a wild desire to “be in style.” But there are good causes for the Panama’s popularity, the chief one being that the common straw hat, with its stiff brim, so universally worn in this country and abroad, is a fragile affair, breaks easily, and has little to recommend it excepting lightness of weight; while a good Panama may be worn a lifetime, can be blocked to any shape, and is exceedingly comfortable to the head. It is, in short, a summer luxury, and only its costliness has prevented it from being universally worn.

Among the false notions regarding Panama hats—and there are prevalent a great many— is that of its origin. The name, in the first place, would lead one to believe that the fabric is manufactured in Panama, whereas the fact is that Ecuador, Colombia, and Guayaquil produce two-thirds of all the Panamas in the market. The city of Panama is merely a shipping port for these hats, which are brought from other places. It is the metropolis of the northern part of South America. The name was originally coined by some French merchants who bought straw hats in the village of Monte Cristo, Ecuador, and took them back to Paris. They attracted attention on the boulevards there, and when queried about them the Frenchmen curtly replied, “Chapeaux de Panama.”

Another illusion that prevails generally is that the natives weave these precious hats under water, but the photographs shown here conclusively disprove that. The rumour probably started from the method of soaking the raw material in water prior to their being woven. There is nothing extraordinary about this, the object being merely to soften the ” straw,” so that it will be pliable and easy to handle.

To call the Panama a straw hat is, by the way, an anomaly, for it is not made of straw at all, the material used in its manufacture being either the stem of palm leaves or a rare sort of grass that grows in South America. The natives are very deft in curing and weaving both these products. The palm they tear in shreds with their teeth until it spreads out fan-shape. After a long soaking the palm stem is taken out of the water and nailed on a rough – looking block, at which the workman sits for weeks at a time, carefully putting in place shred after shred.

It is this length of time and tediousness in labour that account for the high price placed on Panama hats. An idea of the real situation in Panama may be had from the following letter received by S. M. Jackson and Co., of New York, from their South American agent: “Replying to your valued inquiry of April 25th,” said this correspondent, “regarding which we have had to make inquiries, we find that the ‘finest’ hat required by you would necessitate four months to manufacture, and would cost between 80dols. and 100dols. in gold” (£16 to £20). When a hat costs 100dols. in its unfinished condition at the place of manufacture it is not to be wondered at that the same hat, after going through the American Customs house, where a 35 per cent, duty is exacted, should retail at 500dols., or £100.

There is one distinction in Panamas of the utmost importance, a distinction which, if noticed, stamps the wearer as a possessor of the real thing, or, on the other hand, a pretender. Your genuine, high – priced Panama is made in one piece and has no lining, while the inferior style of hat, made for the most part in Antioquia, Colombia, is woven in two pieces and has a lining. The latter is regarded with contempt by the South Americans, though they often pass in the United States for the “real thing” and are priced accordingly.

The perfect Panamas are woven by the women of Ecuador, and those that live in the two provinces of Tolima and Suarez, Colombia. The men can rarely be induced to work, no matter how considerable the pay, and contractors have about ceased trying to galvanize them with energy. But the women are more industrious, and plod along week after week tearing the palm leaf with certain nicety and then weaving in the shreds, one hat at a time.

The value of a hat depends entirely upon its texture and pliability. One that costs £100, for example, should be so closely woven as to appear practically smooth to the naked eye. It is, of course, made in one piece, and if the owner has not been cheated he should be able to squeeze his hat through a finger-ring. But a hat capable of this treatment is about as rare as a blue diamond.

There is no telling where the Panama hat “craze” will end, or the amount of money that has been spent thereon this season. The masculine population seem to have gone quite mad over it, and dealers are taking advantage of the moment to reap a harvest, especially in America. “In other years,” said a Broadway hatter, “I would have sold several thousand stiff – brim Mackinaws in the first part of the season, but this season I have sold less than a hundred. Only Panamas are wanted.

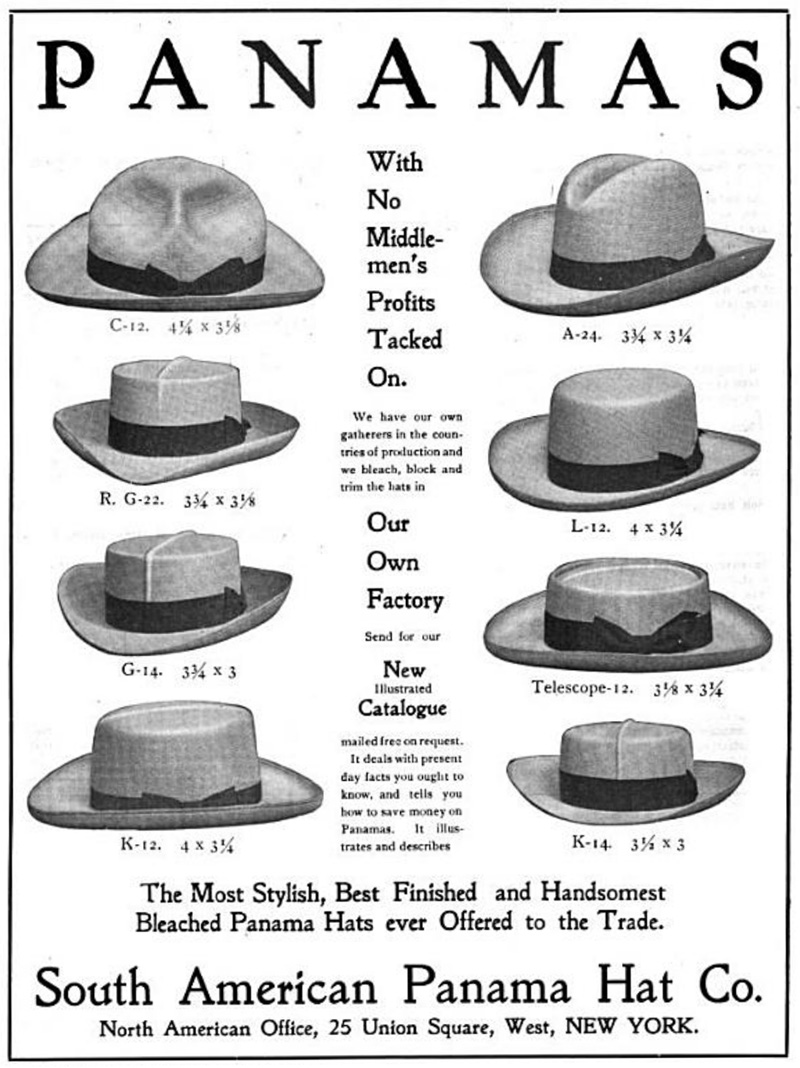

It’s interesting to see that Panama hat sellers were using the “this hat could pass through a wedding ring” marketing line so long ago (you’ll still hear it today). An ad from the time, published in 1905:

One of my own lesser grade hats, which cost about £100 by today’s value – back in 1902 it would have gone for far less.

Comments are closed.